More Pols 335, another film I don’t remember watching. Bob Roberts? Hey, if you say so.

I was reading through for a last edit, and through question after question, I couldn’t for the life of me remember watching the movie, or anything about it. I remember writing this, but not watching what I was writing about. Still I enjoyed the reading. Some legit future-predicting commentary and even jokes about Republicans being old racists. When in doubt, stick with truth if for no other reason than it’s easiest to remember.

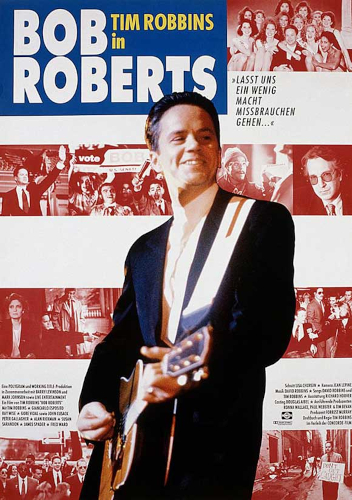

Bob Roberts

- How is the character of Brickley Paiste, the incumbent Senator from Pennsylvania presented?

Sen Paiste in the film is a victim of his own personality. His monologues present a man who is confident and clear-eyed, but egalitarian and detached. He is a genuinely capable representative who is unable to maintain a social relationship with his constituency, and that makes him vulnerable to the more personable message presented by Roberts.

- What does the character played by Jack Black represent?

In my viewing Jack Black represented the obsessive fan or devotee, whose adoration becomes obsession and a need to control the perceptions of others. You can see the shift in his growing anger after initial simple nervousness, to the point where his forehead marking calls to mind thoughts of Charles Manson. My expectation at that point was that Black would be the triggerman at Bugs’ killing; that he would tug a few more political heartstrings by pulling a Jack Ruby on the would-be assassin of his hero’s image. I was a little disappointed to see it be some flunky off-screen.

- What are some of the lyrics of the songs that Bob Roberts sings? How do his political views differ from more traditional protest folk singers like Bob Dylan?

The Roberts lyrics were really quite funny, such as when he gleefully called for drug users to be strung up from tree branches, or at his victory performance where it wasn’t enough to die for God; you had to kill for Him. In other moments the wordplay was more insidious. Beyond his and Eddie Vedder’s continuing to rock in the free world, my familiarity with Dylan is limited to his reputation as the 60s’ incomprehensible arbiter of peace and love. Woody Guthrie’s This Land Is Your Land (1944) would have been right up Dylan’s folk alley as a message of community. Recording his signature mumbly twang to the likes of “this land was made for us, this land was made for me” is a devious trick.

- The film ends with the Woody Guthrie song “I’ve Got to Know” and then the word “Vote” appears on the screen. Lyrics from the song are included on the next page. Why do you think Director and Writer Tim Robbins ended his film this way?

A reading of Guthrie’s lyrics offers a laundry list of things that responsible voters should want to know, questions they should want to ask. In that they are also questions with answers that should be within reach of news divisions backed by corporate titans, the practical application would be to first ask why then are those answers not forthcoming? The answer was provided by David Strathairn a few films ago and thirteen years later- “The fault, dear Brutus, is in ourselves.” (Good Night, And Good Luck, 2003) Having allowed these corporate interests to so cloud our view, it is the responsibility of the voter to consider what they’ve created, and act accordingly.

- How is television news portrayed in the film? What are the anchors like, what news do they cover, and how do they present the scandal involving Senator Paiste?

Casting Susan Sarandon – his own wife – as one of these anchors is indicative of how the film presents news anchors. James Spader, Helen Hunt, Peter Gallagher, these are all very capable actors reporting fluff in the guise of news, sending the camera to one another just to be seen by the camera. Taken as a metaphor, they are an industry wasting its potential. The “scandal” of Paiste’s chauffeuring was allowed to persist in large part due to journalists who sat pat and read from scripts instead of reporting.

- Robbins said of the film Bob Roberts: “It is about entertainment and the co-opting of entertainment.” What does that mean and do you see any similarities to the message in A Face in the Crowd?

This message of the co-opting of media is presented quietly until the conclusion of the film approaches, when reporter Bugs Raplin addresses the camera and encourages vigilance. When brought to the forefront you can look back and recognize the other big tell, the politician running his campaign through entertainment media. In the moment, the commentary of those scenes appeared to be the monetization of politics, but the exposition towards the end suggests the dual meaning. A message of both films is that entertainment is influence, and that audiences allow themselves to be taken advantage of when they blind themselves to how and where they’re being steered.

- Compare the television advertisements for Bob Roberts to the real ones that we have viewed in class and that you have seen elsewhere. How far from reality are the spots shown in the film?

The political ads in Bob Roberts are exaggerations of contemporary campaigns, though the strategies have aged. There was a period from the 80s through the early 90s when television aspired to more artistic heights. Inspired in their way by the creativity of MTV programming like the INXS video appropriated by Roberts, some abstraction and theatricality become common. Sunrises were not uncommon during Ronald Reagan’s “Morning in America” campaign of 1984. The framing of political ads has shifted in the time since due to legislative and commercial preferences. Today’s voters want to see their candidates up close and forge a connection, so frontrunners don’t hide behind metaphor quite as often as they used to.

- The film is also a commentary on what Robbins sees as control of government by the military industrial complex. Discuss examples of this in the film.

These commentaries were essentially spoken word performances by Sen. Paiste and Bugs Raplin. Paiste’s contribution is explicit; he’s looking at the camera and talking directly to me when he speaks of President Truman and the perpetuation of the military-industrial complex. Raplin directly connects the Iran-Contra affair to the Bay of Pigs debacle, but the association of Alan Rickman’s Lukas Hart and Oliver North falls flat. Because the events onscreen present no real consequence to Roberts, there is no lesson to be learned from Hart’s treachery. That absence of political consequence becomes meaningful however as the film ends on the eve of the first Gulf War. The suggestion made is that the real-world conflict is just another power-creating construct that will require no penalty of its architects.

- What does the film say about corruption in politics?

The film’s position – given voice by Raplin – is that corruption has become endemic in American politics. Raplin goes back to Kennedy’s Bay of Pigs, but the genesis of what he decries was likely well earlier. His argument is that…

…when boldfaced political opportunism is uncovered and left unpunished in a meaningful way, the path is cleared for the eventual institutionalization of corruption.

lookin’ at you, Chuck Schumer…

- Bob Roberts is one of the few recent American films that clearly takes sides in politics. Why is it so unusual for American films to have an ideological bias?

There are two sides to this. First is the generalization that American films tend to avoid partisan leanings. This is largely true, due to a commercial need to avoid alienating audiences (customers for the studios’ product). There is also the growing international market for film. Foreign audiences don’t necessarily have an interest in watching American political plays, and they’ve proven to be as profitable as American audiences. Still, even blockbusters will sometimes push that boundary, as when Bill Pullman was obviously far too young to be a Republican president in 1996’s Independence Day, or when Morgan Freeman was far too Black to be a Republican president in Deep Impact (1998). Beyond tentpole territory though, I don’t see political films being shy about preference. Liberals presented as enlightened and conservatives as narcissists, or less frequently liberals as bumbling and conservatives as righteous. Examples of both archetypes play out in the 1985 classics Spies Like Us and The Man With One Red Shoe, but the selection of films for this class alone represents the leftist consistency with which everyone but Kirk Cameron or Mel Gibson tends to approach explicit political themes.