Pols335 Essay 5: And That’s a Wrap.

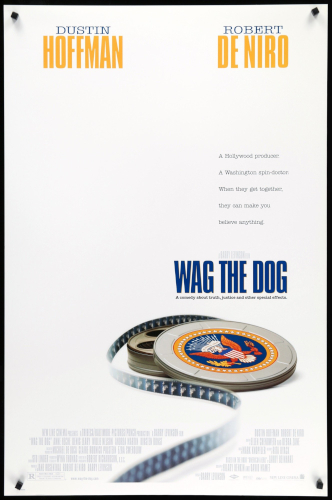

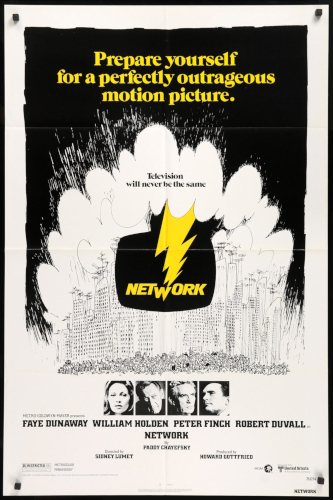

I skipped over a question set from this module, the responses for Wag the Dog. The movie was only ok, and the writing didn’t really add anything to the experience so I gave it a pass. I’m liking the writing here though. “At least he’s not doing drugs” lol. This was the last set from Politics and Film, there was no final essay or anything. Covered in this one were Network and Wag the Dog.

5: Modern Media Manipulation

- Both films feature sinister plots of large, powerful institutions designed to control public opinion for corrupt purposes and both share a very cynical view of mass media and mass public opinion. Compare and contrast these films in their characterization of large powerful global interests?

Network and Wag the Dog each frame corporate media ownership as acting in their own interests over those of any other. The commentary they offer is valid but indirect. Filtered through the lens of satire, some interpretation is necessary, but that interpretation takes away from the force or direction of the film’s criticism; the audience is left to come to their own conclusions based on the jokes they did or didn’t get. This is a curious narrative choice, given the films’ seeming disdain for the comprehension of the common man. Operating as they do under the assumption that audience opinions are easy to mold, the best audience for these films should be the common man they belittle. How else to effect change? Hiding that meaning behind inside jokes or quick dialog only blunts the spread of the message, or at worst inspires resentment of a Hollywood that thinks it’s so smart.

Wag the Dog’s Stanley Motts (Dustin Hoffman) is a stereotypical Hollywood powerhouse, a producer responsible for the creation of blockbusters who has everything he wants except the respect he thinks he deserves. He is knowingly applying his skills to the real-world deception of his audience but beyond that he’s simply doing his job and putting on a convincing show. The tools of media and the caprice of those at the switch are the West-coast villains, but the story’s true bad guy is Robert De Niro’s Conrad Brean. Introduced as a media consultant of some kind, he is revealed to have a long history of involvement with government manipulation of imagery. With this background his evil is less on behalf of corporate greed than it is government self-preservation. Media’s villainy in the picture stems from the ease and joy with which Motts approaches the task of staging a “war” on television. He’s not a bad man at the wheel of a corporate empire, he’s just bored and willing to play in a moral grey area. He’s in it for the challenge. This is not a role model for children, but at least he’s not doing drugs.

On the other hand, Network’s UBS offers an easier target. Even accounting for the hyperbole of satire, their pursuit of the revenues made possible by ratings is singular. In laying the groundwork for UBS’ desperation, an excuse is made for them in their described history of failure. Clearly, this is a network more moved to desperation than would be normal, so the warning of the film is more hypothetical than practical. The arguments made however about the distinctions between news and programming are as relevant as they were in Good Night, And Good Luck. The dire straits faced by UBS only tilt them along the same axis their industry constantly ponders. Along that axis however lies the cautionary tale of mingling news and programming.

Network’s decision to keep anchor Howard Beale on the air after his suicide threat was on ethically shaky ground, but the observation that editorializing has become a respectable contribution is not wrong. Any head-fakes towards rationalization fly out the window however once news is permitted to take on a vaudevillian variety persona. The message being channeled by Beale becomes completely irrelevant at that point, because his words have become secondary to his image as a frothing prophet of middle-class ennui. Is he actually fainting after these rants and wouldn’t that be a bad thing? But the audience only applauds, and their approval is what pays the bills upstairs.

Portraying the Saudis as corporate bogeymen falls flat, though some of that may be due to the passage of time. With fossil fuels on the decline, so is Middle Eastern political influence; Saudi Rockefellers are simply not a clear and present danger to modern eyes. It’s to the film’s benefit that it focuses more on the questionable acts of UBS, as American greed will outlast any international paradigm. For greed is UBS’ tragic flaw. Their willingness to stake industry superiority on the health of a volatile mind, to sponsor the terrorism of the Ecumenical Liberation Army so they could broadcast it, even stripping away the humor one is left with greed, desperation, and narcissism. Robert Duvall’s Frank Hackett is not some idle rich guy looking for a challenge. Hackett wants an edge, his purpose is to dominate. How he goes about that is per the terms of the script, but corporate aggression jumps off the page as recognizable to everyone.

The inclusion of money in politics is a prominent issue for the corruptions it makes possible. Television on the other hand has always been a business, so we see its corruptions as a given. We tell ourselves that we can recognize a commercial when we see one but we fail to recognize the arms race underway between media and audiences. We fail to grasp how motivated and how well-funded networks can be to the purpose of manipulating viewers without triggering their pitch-detecting warnings. The fact is that every plucked heartstring is a carefully scored note. Where those hearts can be moved to generate a profit, there will always be a risk of singular framing (if not outright deception).