(Pols499) Gunning For Votes: Finding Connections Between Campaign Funding and Congressional Support.

My last semester at CSUCI was the first semester of lockdown, and those months got pretty weird. My sense of time got all mushed- that spring break lasted a solid month, basically. Then I had to spend the rest of the semester recovering from dissociating so hard. My capstone got scaled back in a big way as I started to build it out- some due to time constraints, some due to planned complexity that would have killed me. I knew that money and guns would be my subject, but the direction of study took a while to nail down.

Entire chunks of the report material depended on elements from a stats class I was taking during the same semester, and that class became an even bigger crunch than the capstone. I was putting this report – and presentation – together with placeholders dropped in where the math would be. As I figured out the stats material I’d need, I’d go back and drop in the data and then make the wording work. The whole analysis was the last bit to get done, because it wasn’t until everything was almost done that I really understood it :D

The lit review was supposed to be 10 pages, but I had to do some stretching with the material to make it to 8 pages. That was an early source of worry, but I was reasonably confident that good source material was lacking and that I’d covered what I had without milking it too much. There wound up being some room to get creative with the analysis though so I was content. I figured the analysis was where most of the grade would be coming from anyway, the rest was just English. All told the thing came to 25 pages. It’s no PhD dissertation, but it was a nice solid round number to wrap things up with.

Presenting all that here is a different beast, there’s just no way to get around there being a ton of text. Wonder if these links will work…

“Abstract” (generalized paraphrasing improvised over a year afterwards)

The purpose of this study was to ascertain whether a correlation could be found between the campaign contributions of interest groups and the voting behaviors of United States House representatives. Support provided by proponents of looser gun control was weighed against Congressional support for gun control legislation. Previous studies have suggested a connection, sometimes emphatically, but such studies are frequently based on context too specific to generalize. The foundation of this study rests upon separate work with AI systems that has shown predictable trends in voting behaviors, between partisan and financial parameters. The selection of gun control as a subject issue introduced a partisan filter on its own; leaving any financial connections to be isolated for study.

Ultimately the results here were inconclusive. A general correlation was identified, but the volume of intervening factors produces an ambiguity the data alone cannot overcome. In some instances partisanship reigns supreme, and the volume of contributions is affected by the political makeup of the chamber. In other instances votes were essentially symbolic in nature, setting the motivations of the legislators as perhaps equally symbolic. While the study design applied may have introduced errant biases into the data used, a definitive learning may be that even black-and-white issues like life and death can become very uncertain in the political sphere.

Introduction

There is a general consensus that Congressional leadership in the United States is influenced by the spending of motivated private parties, but the depth of that influence is a mystery. Dollar values, combined with commercial allegiances, combined with political allegiances, make possible many external influences on representatives. The clout wielded by groups that exist for the express purpose of exerting political influence has in some ways come to rival the clout once commanded only by the states themselves. There would seem then to be a benefit to the idea of gauging specifically any connections present between spending in support of a candidate and the performance of that candidate on the job. Measures of integrity could be explored, or the agendas of donors made clear. Touching upon our purpose here, activists of all stripes could gain a better understanding of the obstacles in their paths. Our goal is to expand the foundation of data-based corroboration between campaign support and candidate behavior.

The relevant literature reflects the depth of thought applied to the theories of issue advocacy and campaign finance, but there is precious little empirical analysis. Some of that is due to complexities in the theory. The Supreme Court has alternately sought clarity (Buckley v Valeo) and proffered anonymity (Citizens United) to different campaign contributions. Conceptually, sometimes influence is exerted through inaction in the maintenance of a status quo. This leaves the observer with the difficult task of measuring negatives. Alternately, some of the lack of empirical study is a function of the complexities in the practice of campaign finance law. Donors – whether individuals or institutions – have multiple options when it comes to offering financial support to furthering their causes, and each of those options exert influences with differing levels of transparency. Causes or candidates are just as frequently opposed by parties or factions similarly supported by varying degrees of transparency, and even then not all opposition is direct. Even with the benefit of hindsight it can be difficult to understand which levers of power were pulled, which were held, and who paid.

Addressing this corroborative shortfall requires stepping into new territory. The shifting influence of political parties must be factored in. There is quantitative study of the influence of the gun lobby on legislators, but such studies are notably limited in scope and timeliness. New models are being constructed to wade through the complexities between legislative support and legislative action, with machine learning applied to parsing the sometimes thousands of variables involved. One such study has found promising results in correlating the voting patterns of officials to their campaign contribution data, seeing distinctions even through the influence of partisanship. This study seeks to build upon that newfound understanding with an inquiry from the industry perspective. Using campaign contribution data and Congressional roll calls, I will explore whether a connection can be identified between the campaign contributions of firearm manufacturers and the voting records of United States congressmen on gun-regulating legislation.

Literature: Theory and Practice

The study of campaign finance lies at an intersection of theory, practice, and ambiguity. Every election is a portrait of the social, legal, political, and financial pressures that are unique to that moment. The changes to these triggers between cycles is sometimes a function of social drift, and sometimes a result of structural change. Whereas times of social drift can provide value in illustrating the influence of events, structural change is disruptive. In studying the influence of money on elections, one invariably runs into difficulties with reproducibility thanks to these ever-changing times. To establish a common foundation for study, it is necessary to rely on texts that connect more to the descriptive elements of the subject than to actual dollar figures. These books and articles represent the results of the social sciences that were explored as laws were being passed and rulings made.

Campaign finance law has changed considerably since the Court decided Buckley vs Valeo in 1976. Their ruling was very much a split decision; restrictions on some forms of giving were lifted, while others were affirmed as necessary. The influence of political partisanship has changed over that time as well, at its own pace. These changes make the relevance of 1976 debatable in 2020. But Buckley’s split decision establishes two key premises that remain central to campaign finance assumptions to this day. The Court upheld limits on giving to candidates and disclosure requirements. Those limits remained in place to support the Court’s determination that they allowed “voters to place each candidate in the political spectrum more precisely than is often possible solely on the basis of party labels and campaign speeches” (Buckley v. Valeo, 1976). Those premises contribute to expectations that modern practice can be measured against. Inherent in their ruling is the estimation that political giving is proximate to political patronage.

The subject of the strength of outside influence was relevant to the Court in Buckley. The parameters they set between different types of advocacy were based on the estimation that “independent advocacy does not presently appear to pose dangers of real or apparent corruption” (Buckley v. Valeo). Lilian BeVier uses this as an argument that the regulation of indirect advocacy is an unnecessary overreach in “The Issue of Issue Advocacy” (BeVier, 1999). Indirect spending – that is, money that is spent for the purpose of garnering influence, but paid to someone other than the voting official – makes things even more unclear, as there are multiple forms. As described by Richard Briffault, “Although some lobbyists are powerbrokers in their own right, for the most part that influence is deployed on behalf of lobbyists’ clients.” (Briffault, 2008) Thus the activity of lobbyists, sometimes derided for their dealmaking reputations, becomes just another form of outreach between advocacy and governance.

The inherent value of speech is debatable; context matters. In both Buckley and Citizens United, the Court identifies different forms of political giving as different types of speech. There are stricter direct limits for corporations and unions, for example, than there are for individual donors (Briffault, 2008). It was believed by the Court that the financial resources of those entities present an influential weight equal to or superior to that of any logical argument- that the dollars would literally speak louder than words. At the same time, the Court has not seen fit to limit industry’s ability to use indirect political spending as a means to “cast their voice to the wind” and be “heard”.

Thus have arisen “SuperPACs”, or political influence entities that can act as legal go-betweens, facilitating communication between lawmakers and otherwise sanctioned petitioners. These organizations are entities of substance, and have come to be funded by millions of dollars, year after year. They present a change to the nature of political influence, according to Garrick Pursley. He describes these groups as being of such wealth that they command premium levels of attention from lawmakers (Pursley, 2014). The strength of that influence is such that it competes with the district-related business to lawmakers are elected to attend. Essentially, he argues that these Political Action Committees have the capacity to rival the states in their ability to steer national policy.

This concern may be an exaggeration, but it is a reality that governance is driven by balanced interests. The biased pluralism (Gilens & Page, 2014) that dominates our practice of politics is an outgrowth of a federal system that encourages competition and overlapping spheres of influence. It raises legitimate questions of clarity however. Frank Baumgartner describes that difficulty to parse the influence being wielded. In his own study he examines the proposal that so many complexities have arisen, that there is no identifiable linkage between lobbying resources and policy outcomes (Baumgartner, Berry, Hojnacki, & Leech, 2010). What he found was indeed ambiguous, and suggested that interpersonal connections could be just as influential.

That in turn brings us back to the differing reporting requirements attached to different means of support. The looser requirements for indirect forms of giving mean that less is known about who is speaking, and to whom. Study by Fuyuan Shen and H. Denis Wu suggests a measurable effect of third party issue spending on lawmaker preference (Shen & Wu, 2002), but we are limited in our ability to know who lawmakers are hearing through that process. It brings us as well to the next relevant dimension, that of peer connections and political parties.

As Anne Baker describes, there are network of people and overlapping interests involved in the campaign contribution process. Those people through this process can become invaluable resources to one another (Baker, 2014). Sometimes those connections are to donors, and sometimes they are to ideological peers, i.e. political parties. Our political parties have long been flies in the federal soup, agendas to compete with the power-management mechanisms built into the Constitution. These affiliations were telling, but not necessarily determinative. The Court stated as much in Buckley. The influence of partisanship has shifted alongside the laws and rulings that have shaped the landscape. Party (peer) influence has always been a factor; we are social creatures. Miguel Pereira and Daniel Butler demonstrate that party affiliation can mean life or death for a policy proposal. Officials are more likely to support an issue if a copartisan does, and less likely to be dissuaded by other influences (Butler & Pereira, 2018). But the influence of those copartisans has not been a constant. In contemporary politics, partisan allegiances have been more sharply defined by a more confrontational practice of politics. The impeachment of President Bill Clinton by a Republican congress in 1998 was a bellwether moment. As a political process it did not happen in a vacuum, but in some ways the parties have been taking turns retaliating ever since.

Cumulatively these lawmakers of ours, with their different social and political allegiances, are pressured in their work by interest groups and industries with their own complex web of practice. The weight of that influence is made vague by its varying intent. David Lowery argues that we need to challenge our own understanding of the idea of influence (Lowery, 2013). In a paradigm of biased pluralism, influence is balanced on all sides by competing pressures. Sometimes that influence is used as a preventative measure, to discourage the agendas of other from progressing. This makes it necessary to prove (or assume proof of) negatives, without knowledge of what balancing mechanisms are at work.

This brings us to the present, a time in which political parties can have singular influence over platform issues. A time in which money can flow from the pockets of business and to the attention of officials in any number of ways. For better or worse, it is a time more of social drift than of disruptive change. With an understanding of the different structures involved, now becomes a good time to ask whether any patterns can be identified in the measurements made during that drift.

Relevant specifically to the influence of the gun lobby, two studies illustrate the challenges described in this type of research. Leo Kahane in 1999 demonstrated that the “political activities and presence of the National Rifle Association had a significant impact on the voting patterns by Senators” on gun-related legislation (Kahane, 1999). Just in review of the abstract there would appear to be a strong corroboration of our developing research. Unfortunately his results are of limited use in the present. That “time” distinction is most important, as the legislation studied was back in 1993 and 1994. This was prior to the financial landscape designed by Citizens United, and prior to the “Republican Revolution” that changed the face of partisanship. Then also his conclusions are drawn from the passage of two bills over a two-year span. Those conclusions may therefore be as contemporaneous as the intents of those specific voting representatives. This is not to suggest his conclusions are invalid, but that they are due to be revisited considering the change in foundational circumstances.

In 2002, a study on gun-related legislative behaviors was conducted, looking at a larger sample (all gun legislation between 1992 and 2002) through a wider lens (partisanship, finance, gender, etc.) and again found “strong and consistent” (Price, Dake, & Thompson, 2002) relationships between officials’ positions and their sources of support or identity. There is value and opportunity in their results as well, however. As with Kahane’s results, these are from a period of time with structural dissimilarities to the present. They are notable as well for coming entirely from within the years of the Clinton administration, so they may reflect singular partisan interests. Such a possibility is hinted at in an abstract that casts the gun lobby as successful despite public opposition, without considering the form of that opposition. If someone brings a knife to a gunfight, do you blame the guy with the gun when he wins? It is difficult to maintain the argument that the gun lobby maintains an unfair advantage while overlooking the reluctance of credible opponents to engage on the same level.

Taken together, these two studies offer us a suggestion for future research. Perhaps a more inclusive or more current period of study would produce more meaningful or even more actionable results. Perhaps a shift in framing would remove a subjective partisan construct. The work done by Price, Dake, and Thompson speaks just as effectively to the challenges of such research. There are hundreds of lawmakers involved over the span of decades, and the changing laws involved mean that different data has been captured at different times. Proper study becomes a very complex process.

Recent work by Adam Bonica at Stanford looks to examine these complex interactions with a technological microscope. He starts from a similar foundation, exploring the practical reality of votes against the determinative clarity desired in Buckley. He points out that competing views have arisen, citing studies purporting that financial clarity does not provide the benefits assumed. Into that space he applied a technological perspective. That coded view required the overcoming of the same small-sample conditions that challenge such study. He notes, “a well-known limitation of roll-call-based measures of ideology is that they are confined to voting bodies” (Bonica, 2018). In the context of his study, that meant incorporating data from legislative voting bodies other than Congress. That will not be a practical application here, but the larger data sample – 20+ years of additional data – should be more revealing than the shorter windows examined previously.

Bonica’s findings are directly connected to the premise of this study. By applying machine learning algorithms to the data mines of campaign contributions and voting records, he found that patterns began to emerge. To the purpose of that study, a connection was made between the sum of donations to a candidate and their likely voting record on subject issues. The designed system was able to identify both subject- and partisan- leanings based on financial data, which furthered the ability of this science. That study on the prediction of roll-call scores offered a proof of the court’s assertion in Buckley, that financial cues can be key identifiers. While our purposes diverge, his results speak to the potential for clear causal connections between finance and influence.

The subject being examined here is from the industry side, to see if any similar correlations between spending and voting could be made from the outside looking in- what is it that industries get for their money? The availability of more data over more time is an opportunity to revisit null hypotheses established before such data was available. While her work is not in the literature, the lectures by Professor Baker at CSU Channel Islands have noted more than once that there is a need for such null-confirming science. This study will seek to both advance the nature of the work underway, and validate the assumptions that ground it.

Study design

Similar to how the direction of this research was informed by the literature, its study was shaped by the data available. Bearing in mind the volume of data involved, an early decision was to limit the scope of this study to the United States Senate. The expectation was that the lower number of senators (100, to 435 representatives) and fewer elections (33 every two years, to 435) would facilitate this process more effectively. The donor databases used by Adam Bonica at Stanford were publicly accessible; their use would provide this study with a comparable foundation. Unfortunately, neither the Senate nor the Stanford data would be applicable.

The donor records were available and very thorough, but their accuracy was a barrier here. There was simply too much information. Bear in mind here the increases in personal solicitations made by the presidential campaigns of Barack Obama and Bernie Sanders. Their overwhelming success at cultivating individual support has added overwhelming numbers of lines to the spreadsheets that keep track of who gave what to whom. As a result, these databases were available but functionally out of reach. The 1990 database was several hundred megabytes in size, the 2016 database was 24 gigabytes. That volume was an insurmountable barrier to the memory in my workstation.

The Senate provided complications as well. Contribution data is attached to the election year for which that support was intended. So when only a third of the Senate is up for election with every cycle, only a third of the contributions made to candidates are attached to the records for that cycle. Additionally, the staggered six-year cycles made time an insurmountable uncertainty- the amounts given to elect someone in 2000 provide a third of the influence on votes in 2006, alongside amounts given in 2002 and 2004.

Between these barriers, both expected sources of data were replaced, to the benefit of this study. The Stanford databases on individual donors were replaced with the aggregated results provided by OpenSecrets.org. Because their data was already organized by interest group and legislative body, the number of lawmakers in the House of Representatives (435 times X) was no longer a barrier to data collection. A shift in focus to the House gave clarity to the results. Because the entirety of the House is elected every two years, single-cycle political giving can be tied more explicitly to political outcomes.

The dollar figures reported by OpenSecrets are in contemporary values that subject the result to an inflationary skew. Such increases in value are not matched in the voting data, so all dollar amounts used for correlating were adjusted for inflation back to 1990 values.

With the study population and independent variables identified, the dependent variable – legislative outcomes – required configuration. From within the term of each elected congress, a gun-related vote was identified. The selections of these votes were based on different criteria. Where the literature was in consensus on the import of a law (The Brady Bill, the Assault Weapons Ban), those votes were captured. In the absence of landmark legislation, votes were selected on a first-found, first-used basis. Two cycles – 1996 and 2014 – were dropped for an absence of found votes.

Vote tallies were recorded for our use in terms of industry share. That is, the number of votes cast in alignment with industry preference. For example, if a gun control bill were to fail, the number of votes cast for its defeat were recorded as the industry-favoring share. If a gun rights bill were to pass, the number of votes behind that victory was recorded as the industry share. This data configuration reflects the amount of influence exerted through electoral cycles on the legislative output of the House- “amounts paid” and “amounts purchased”. Those industry-centric results were then re-configured as percentages or other permutations to test different avenues for correlation. The data used are noted in the appendix, Table 3.

The profile assembled will be examined for correlations using a nondirectional 2-tailed study, to test the research hypothesis (H1 : rxy ≠ 0 ), that a relationship greater than zero can be demonstrated, with p < .05.

Study results

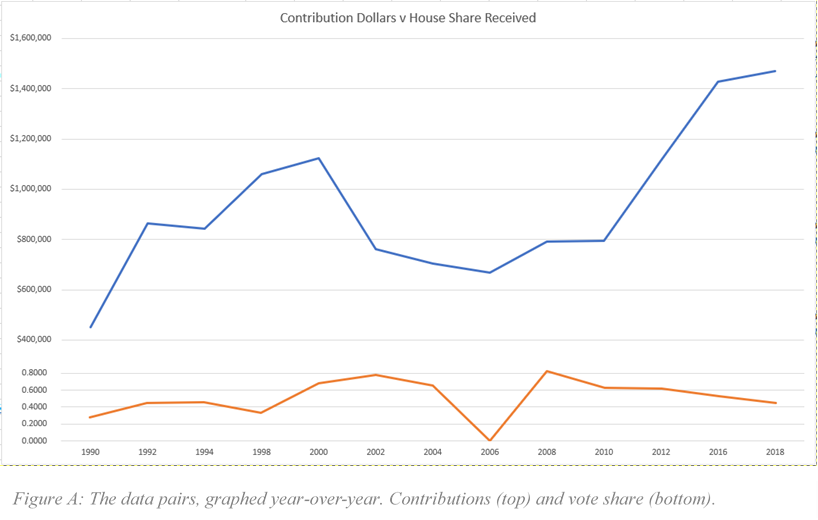

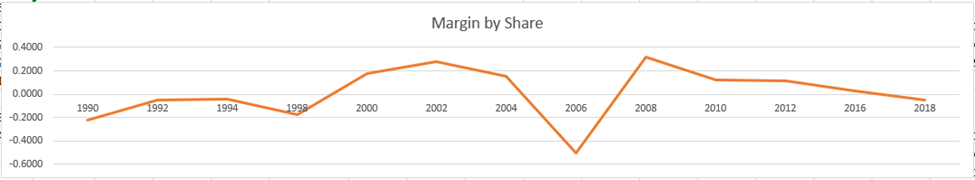

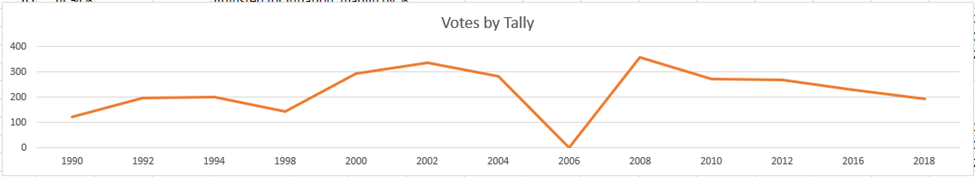

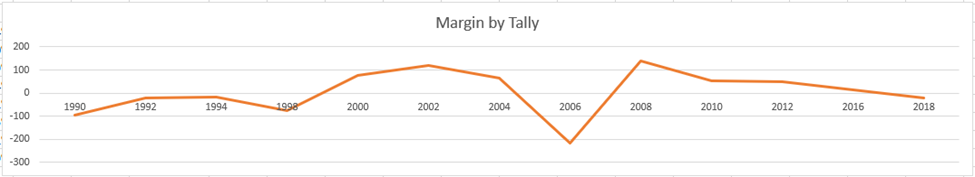

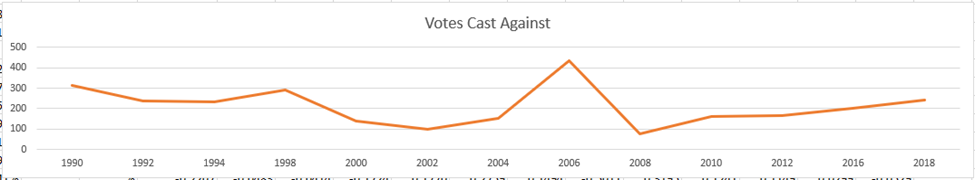

Year by year, the voting and contribution data show some rough correlations (fig. A). An increase, a dip, and a recovery on both lines. The initial results stem from this look. The vote data here is the percentage of support received, this was one of five different permutations of the vote data. All of the other graphs (figs 1-4, appendix) are derived from this same pattern. Whether as a tally or a percentage from any point, the vote data produces identical trend lines,

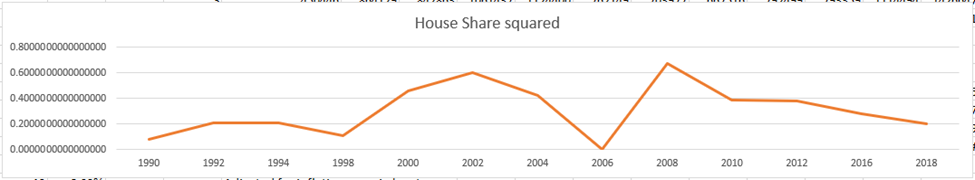

and identical correlation data. The one exception is the opposing vote count, which produced a logical inversion of the direct results (fig 5, appendix) After this initial review, there are essentially single correlations being tested, between the contribution data and the “vote data”, collectively..

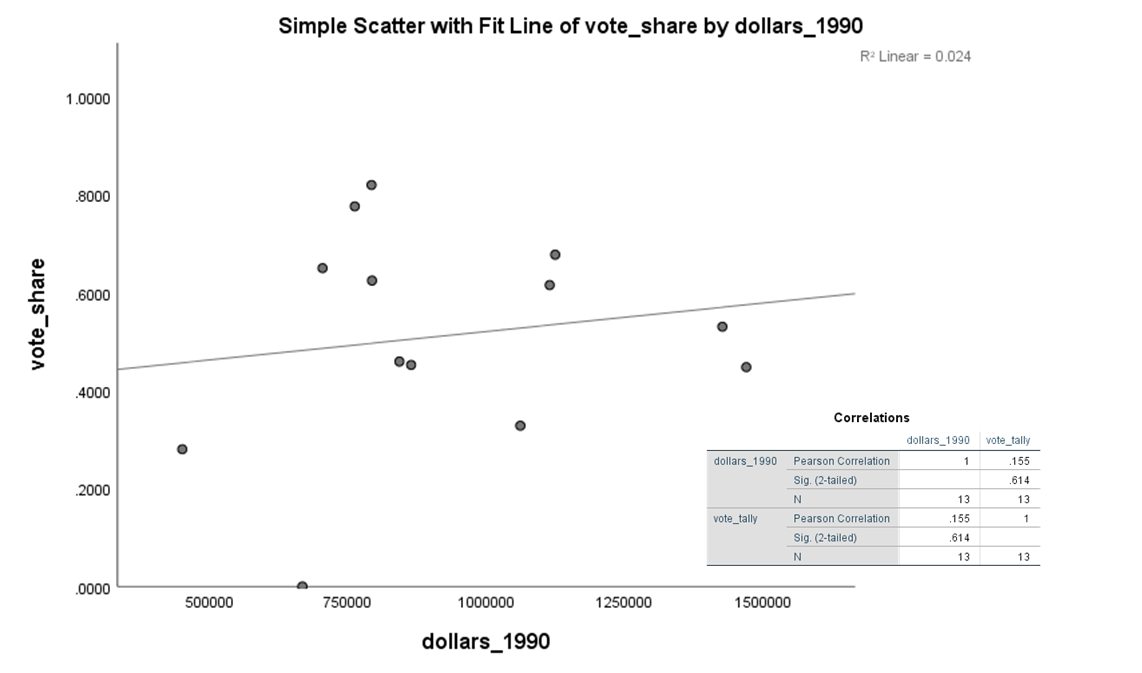

…(fig. B) shows the statistical results of that search for relationships. The linear regression of the scatterplot demonstrates clear directionality, though the slope of that direction belies uncertainty. The metrics involved reinforce this assessment. A Pearson correlation of the voting and donation data shows a correlation strength of only .155. The resulting coefficient of determination (.024) indicates that over 97 percent of the variation in the voting data is attributable to causes other than the contribution data.

This interpretation of validated results however, is not easily reconciled with the disruptive structural changes recorded in the literature. Since the start of the data, there have been significant changes to the relevance of political parties, and to campaign finance law. Beginning roughly with the “Republican Revolution” in the mid 90’s, political affiliations have become more defining than they had been in 1976. In 1993, there were 53 Republicans who voted in favor of the handgun restrictions in the Brady Bill. In 2019, there were only 8 Republican votes in support of the “Bipartisan Background Checks Act”[1]. The Court’s ruling in Citizens United (2010) struck down limits in political spending; enabling the ~33% increase in industry spending the following cycle ($1,331,213 in 2010, $1,968,837 in 2012).

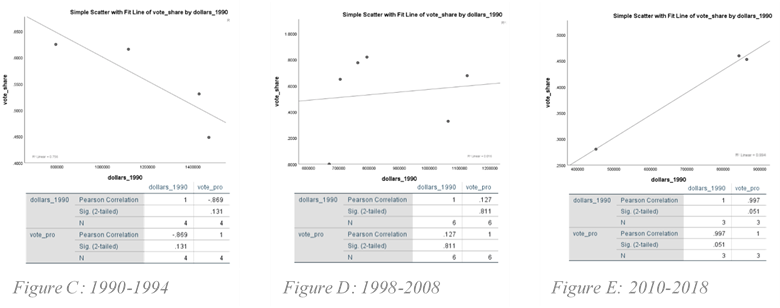

Using these two milestones, it is possible to segment the study period into three distinct sections. There are the votes prior to 1995 (fig. C), votes from 1995-2010 (fig. D), and those from 2010 to the present (fig. E). The same data used for the initial view was broken down into those buckets and checked for any self-contained correlations.

These segmented results suggest different conclusions than those of the larger comparison. Here the correlations take a journey, from strong positive to strong negative, with shifts in significance along the way. A narrative can be constructed of increasing disorganization from one segment to the next, but such a conclusion would present the same risks as those in the decades-old analyses of gun lobby influence. In the earliest sequence there are only three cycles, scant improvement over the two bills studied by Kahane in 1999. The years of partisan escalation roughly correspond to the administration of George W Bush, so there is the possibility there of a partisan skew akin to the Clinton-centric data studied in Price et al. in 2002. The four cycles following Citizens United present an intuitive dilemma, that support from Congress could definitively decline as their support from industry increased.

These known uncertainties within the shorter periods may leave the overall result as the more accurate one. All of the same variables are present, minus constructs that may cause inaccuracy by discounting continuity.

Limitations and opportunities for future study

Some of the ambiguities inherent in this research have already presented themselves. There are the mathematical complications of small-sample studies, in which outliers or even notable standouts can substantially change outcomes. Then there the inability to prove a negative. The cycles in which no recorded votes could be found could be victories for the gun lobby in holding off greater control, or losses in pursuit of greater freedoms. Either outcome could contribute meaningfully to the overall result, but neither could be validated.

It is possible that the voting data does not represent what this study assumes it does. Part of this is because congressional voting is a political process, in which votes can be traded across bills, or cast with differing degrees of intent. During cycles with multiple bills, the exclusion of all but one may be casting out relevant data as noise. The chance of a vote’s inclusion may impose too great a penalty on accuracy. And while sometimes votes are cast strategically, sometimes entire bills are strategic. The 2019 Background Check Act for example stood no chance whatsoever of being advanced by a gun-favoring Senate or White House. Knowing that, there is any amount of symbolism or other intent that may be reflected in those votes beyond support or disapproval of the bill.

Additionally to voting data concerns there’s the fact that not all gun bills are gun bills. Of the legislation selected for study, 3 bills were instances of notable gun legislation amended to other bills. So the support or opposition captured for that bill might be more rightly (somehow) filtered through whatever baggage is attached to the bill’s actual purpose. The attachment of terms to any “must-pass” legislation like spending bills might produce inflated indicators of support in their results.

It is possible that the contribution data does not represent what this study assumes it does. The figures reported by OpenSecrets are those amounts reported as given to candidates. But changes to the law have made it much easier for support to be produced indirectly. The money spent by the industry lobby on advertising or member services promotes public support. A strategy available to any interest group is to pitch their cause to the public, and then present the goodwill they’ve collected as a carrot to legislators. In this fashion, the contribution data represents an unknown fraction of the entire amount leveraged for congressional influence. This adds a dimension of uncertainty to the idea of industry influence as an inherent problem. Regardless of whatever consumer biases may be at play, or how much was spent for their favor, representatives are supposed to respond to the interests of citizen groups. Venturing into straw man territory, if the lobby were to shift entirely to a model of indirect support, then public will would be the primary driver of a representative’s choices. Would those choices be any less legitimate for the root source of their funding? If so, does that not de-legitimize the choices made by individual voters?

Speaking directly to the value of future study is the circumstance of gun control being a largely single-advocacy group. On a financial level, there is no balancing spending pressure. There are the contributions made by the “gun lobby”, and there are the choices made by officials. In 2018, the “gun rights” sector contributed $2,851,417 to House elections; that same year the “gun control” sector contributed $302,750[2]. That imbalance of support may limit the generalizability of these results to particular issues. The presence of balacing advocacies adds a normalizing pressure; as Bonica describes, “the presence of issue constraint means preferences are correlated across issues.” (Inferring Roll-Call Scores from Campaign Contributions Using Supervised Machine Learning) In other words, it is the commonality of balanced opposition that makes these legislative choices comparable.

The “single advocacy” condition presents additional complications. Study by Price et al. of the Clinton years illustrates some of this dynamic in its framing. In their abstract, they note that “recent research has shown strong public support for strategies to regulate firearms yet effective federal legislation to control firearms has been limited.” (Price, Dake, & Thompson, 2002) This premise assumes as fact that the outcomes of legislation are incompatible with the preferences of the electorate, without exploring the assumptions being made. Their work is presented as partisans, from within a political argument; as people, they are “the public” whose wants aren’t being represented. A “gun rights” or “small government” advocate might find their wants being met, but Price positions those potentially diverse perspectives into a single voice of opposition to “the public”. This is inherent in a single-advocacy situation such as gun control. Between the manufacturers and interest groups, the “gun rights lobby” is an organized and established entity. The “gun control lobby” isn’t as clearly-defined. Redirecting this study to issues with more defined “for” and “against” establishments may provide more independent results and constrain the equations to more common terms. Fewer subjective estimations of “us vs them” and more objective observation of “them vs them”.

Applying additional lessons, the influence of political partisanship merits study all on its own. There are some issues that draw broad bipartisan support or opposition, other issues (such as guns) rest almost entirely within single parties. The subject of gun rights appears to be one such issue, but it’s worth noting that the lobby gives to Democrats as well. While collecting the voting data it was noted anecdotally how there are more generally more Democrats willing to support gun rights than there are Republicans willing to support gun control. So in this instance, political parties wield a singular but variable level of influence. Garrick Pursley expressed concern about the clout of political action committees coming to usurp the policy prerogatives of the states (Pursley, 2014). The clout available to parties presents similar risks; existential threats are always important candidates for study.

This study does not look to advance the detailed use of artificial intelligence or other cutting-edge analytical tools, but these directions present great potential value. It is an undeniable fact that there are a great many factors that weigh on the outcome of a 435-seat vote. Technology has a capacity to see a connection between ‘point a’ and ‘point zzq’ that might go forever unnoticed by the human eye. Ongoing attention is vital for these new areas of research. If results like those of Mr Bonica’s remain square to ongoing data streams, then the strength of money’s influence on politics can become far less mysterious. At present, that area of study offers perhaps the best solution to the problem posed by Buckley vs Valeo– how to have a free marketplace of ideas at work in the Congress, without losing clarity to the agendas involved.

Appendix

Table 1, study sources

| Article Name | Author | Year | Level | Source | |

| Inferring Roll-Call Scores from Campaign Contributions Using Supervised Machine Learning | Bonica, Adam | 2018 | Primary | Journal Article | |

| House Roll Call votes | GovTrack.us | 2020 | Primary | Website Multiple pages | |

| Sample bill profiles | GovTrack.us | 2020 | Secondary | Website Multiple pages | |

| Gun lobbies and gun control: Senate voting patterns on the Brady Bill and the assault weapons ban | Kahane, Leo | 1999 | Primary | Journal Article | |

| Gun Control; Gun Rights contributions | OpenSecrets.org | 2020 | Primary | Website Multiple pages | |

| Congressional Voting Behavior on Firearm Control Legislation: 1993-2000 | Price, James; Dake, Joseph, Thompson, Amy | 2002 | Primary | Journal Article | |

| The Campaign Finance Safeguards of Federalism | Pursley, Garrick | 2014 | Secondary | Journal Article | |

Table 2, bill profiles

| 1990 Crime Control Act (gun-free school zones) | |

| Directed the attorney general to develop a strategy for establishing “drug-free school zones,” including criminal penalties for possessing or discharging a firearm in a school zone. Outlawed the assembly of illegal semiautomatic rifles or shotguns from legally imported parts. https://www.govinfo.gov/content/pkg/STATUTE-104/pdf/STATUTE-104-Pg4789.pdf | PUBLIC LAW 101-647 S.3266 Opposed by lobby Passed with 313 votes https://www.govtrack.us/congress/votes/101-1990/h534 |

| 1993 Brady Handgun violence protection act | |

| Amends the GCA (1968) to mandate background checks by licensed seller, established the national instant criminal background check system. Imposed a 5-day waiting period. https://www.govinfo.gov/content/pkg/BILLS-103hr1025eas/pdf/BILLS-103hr1025eas.pdf | HR 1025 Opposed by lobby Passed with 238 votes https://www.govtrack.us/congress/votes/103-1993/h614 |

| 1994 Public Safety and Recreational Firearms Use Protection Act | |

| Part of larger violent crime package, known as an assault weapons ban. Prohibited sale and manufacture of 19 different assault weapons and high-capacity hardware. (expired 2004) https://www.govinfo.gov/content/pkg/BILLS-103hr3355enr/pdf/BILLS-103hr3355enr.pdf | HR 3355 Opposed by lobby Passed with 235 votes https://www.govtrack.us/congress/votes/103-1994/h416 |

| (1996 cycle, none found) | |

| n/a | |

| 1999 Reacquisition Background Checks (amendment) | |

| Requires background checks when firearms are reacquired from lien. https://www.govinfo.gov/content/pkg/BILLS-106hr2490enr/pdf/BILLS-106hr2490enr.pdf | PL 106-58 Opposed by lobby Won with 292 votes https://www.govtrack.us/congress/votes/106-1999/h426 |

| 2002 Homeland Security Act | |

| Creates ATF, gives pilots guns https://www.govinfo.gov/content/pkg/BILLS-107hr5005enr/pdf/BILLS-107hr5005enr.pdf | HR 5005 Supported by lobby Won with 295 votes https://www.govtrack.us/congress/votes/107-2002/h367 |

| 2003 Tiahrt Amendment (amendment) | |

| Prohibited the ATF from publicly releasing sale information for criminal purchases. A liability shield for sellers and manufacturers, as full discovery was prohibited by statute. https://fas.org/sgp/crs/misc/RL32842.pdf, p109 | Supported by lobby Passed with 338 votes https://www.govtrack.us/congress/votes/108-2003/h32 |

| 2005 Protection of Lawful commerce in Arms Act | |

| Prevents manufacturers, distributors, dealers, importers from being named in suits involving their products. Dismissed pending cases. https://www.govinfo.gov/content/pkg/STATUTE-119/pdf/STATUTE-119-Pg2095.pdf | PUBLIC LAW 109–92 Supported by lobby Passed with 283 votes https://www.govtrack.us/congress/votes/109-2005/h534 |

| 2007 NICS Improvement Amendments Act | |

| Improves background check system https://www.govinfo.gov/content/pkg/BILLS-110hr2640enr/pdf/BILLS-110hr2640enr.pdf | HR 2640 Opposed by lobby Passed 100% https://www.govtrack.us/congress/bills/110/hr2640 |

| 2009 Credit Card Accountability Responsibility and Disclosure Act (amendment) | |

| Allowed guns in national parks https://www.govinfo.gov/content/pkg/BILLS-111hr627enr/pdf/BILLS-111hr627enr.pdf | HR 627 Favored by lobby Passed with 357 votes https://www.govtrack.us/congress/votes/111-2009/h228 |

| 2011 National Right-to-Carry Reciprocity Act (never signed into law) | |

| Concealed carry reciprocity- permits issued in other states will be honored in non-carry states. https://www.govinfo.gov/content/pkg/BILLS-112hr822rfs/pdf/BILLS-112hr822rfs.pdf | HR 822 Supported by lobby Passed with 272 https://www.govtrack.us/congress/votes/112-2011/h852 |

| 2014 SHARE Act (never signed into law) | |

| To protect and enhance opportunities for recreational hunting, fishing, and shooting. https://www.govinfo.gov/content/pkg/BILLS-113hr3590pcs/pdf/BILLS-113hr3590pcs.pdf | HR 3950 Supported by lobby Passed with 268 https://www.govtrack.us/congress/votes/113-2014/h41 |

| (2014 cycle, none found) | |

| n/a | |

| 2017 Concealed Carry Reciprocity Act (never signed into law) | |

| Requires concealed carry permits to be honored in other states (repackaging of 2011 effort). https://www.govinfo.gov/content/pkg/BILLS-115hr38rfs/pdf/BILLS-115hr38rfs.pdf | HR 38 Supported by lobby Passed with 231 votes https://www.govtrack.us/congress/votes/115-2017/h663 |

| 2019 Bipartisan Background Checks Act (never signed into law) | |

| Requires a background check for every firearm sold. https://www.govinfo.gov/content/pkg/BILLS-116hr8pcs/pdf/BILLS-116hr8pcs.pdf | HR 8 Opposed by lobby Passed with 240 votes https://www.govtrack.us/congress/votes/116-2019/h99 |

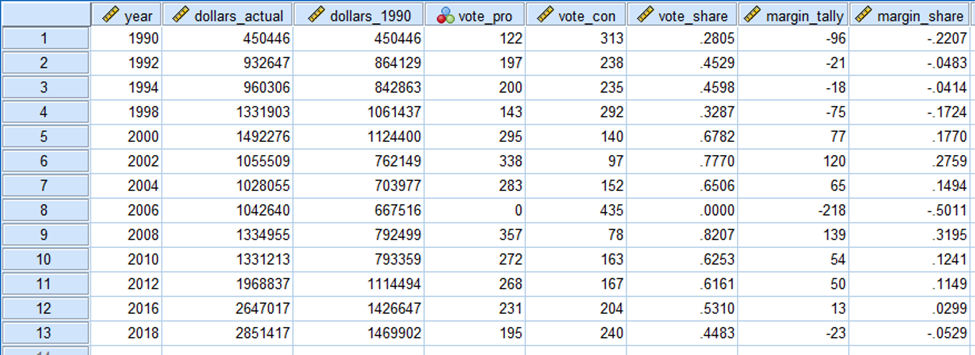

Table 3, data table (SPSS)

Figures 1-4, alignment of the voting data around shifting axes

Figure 2

Figure 3

Figure 4

Figure 5, an inverse curve is produced by the charting of the vote_pro data.

Literature: Works Cited

Baker, A. E. (2014, Dec). Party Campaign Contributions Come with a Support Network. Social Science Quarterly, 95(5), 1295-1307. doi:10.1111/ssqu.12067

Baumgartner, F. R., Berry, J. M., Hojnacki, M. E., & Leech, B. L. (2010, Jan). Lobbying and Policy Change: Who Wins, Who Loses, and Why. University of Chicago Press. doi:10.7208/chicago/9780226039466.001.0001

BeVier, L. R. (1999, Nov). The Issue of Issue Advocacy: An Economic, Political, and Constitutional Analysis. Virginia Law Review, 85(8), 1761-1792. From https://www.jstor.org/stable/1073938

Bonica, A. (2018, Oct). Inferring Roll-Call Scores from Campaign Contributions Using Supervised Machine Learning. American Journal of Political Science, 62(4), 830-848. doi:10.1111/ajps.12376

Briffault, R. (2008). Lobbying and Campaign Finance: Separate and Together. Stan. L. & Pol”y. Rev, 19, 105-129. From https://scholarship.law.columbia.edu/faculty_scholarship/916

Buckley v. Valeo, 424 US 1, 75-436 (Supreme Court Jan, 1976).

Butler, D., & Pereira, M. (2018, Sep). TRENDS : How Does Partisanship Influence Policy Diffusion? Political Research Quarterly, 71(2). doi:10.1177/1065912918796314

Congressional Donors and Campaign Reform. (2003). In P. Francia, J. C. Green, P. S. Herrnson, L. W. Powell, & C. Wilcox, The Financiers of Congressional Elections (pp. 140-156). Columbia University Press. From https://www.jstor.org/stable/10.7312/fran11618.10

Gilens, M., & Page, B. (2014, Sep). Testing Theories of American Politics: Elites, Interest Groups, and Average Citizens. Perspectives on Politics, 12(3), 564-581. From https://www.jstor.org/stable/43281052

Kahane, L. H. (1999, Dec). Gun lobbies and gun control: Senate voting patterns on the Brady Bill and the assault weapons ban. Atlantic Economic Journal, 27, 384-393. From https://doi.org/10.1007/BF02298335

Lowery, D. (2013). Lobbying influence: Meaning, measurement and missing. Interest Groups and Advocacy, 2(1), 1-26. doi:10.1057/iga.2012.20

Price, J. H., Dake, J. A., & Thompson, A. J. (2002, Dec). Congressional Voting Behavior on Firearm Control Legislation: 1993-2000. Journal of Community Health, 27, 419-432. From https://doi.org/10.1023/A:1020601218452

Pursley, G. B. (2014). The Campaign Finance Safeguards of Federalism. Emory Law Journal, 63, 781-855. From http://law.emory.edu/elj/_documents/volumes/63/4/articles/pursley.pdf

Shen, F., & Wu, H. D. (2002, Nov). Effects of Soft-Money Issue Advertisements on Candidate Evaluation and Voting Preference. Mass Communication & Society, 5(4), 395-410. doi:10.1207/S15327825MCS0504_02

[1] Brady Bill https://www.govtrack.us/congress/votes/103-1993/h614

Bipartisan Background Checks https://www.govtrack.us/congress/votes/116-2019/h99

[2] Gun rights portal (OpenSecrets) https://www.opensecrets.org/industries/summary.php?ind=Q13++

Gun control portal (OpenSecrets) https://www.opensecrets.org/industries/summary.php?ind=Q12++