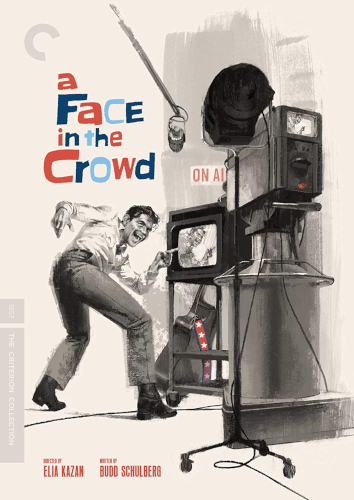

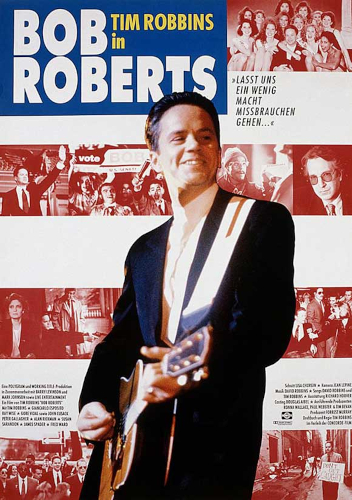

Another 335 essay: Bob Roberts is A Face in Every Crowd

- Compare the character of Lonesome Rhodes from A Face In The Crowd with the title character in Bob Roberts. What do these characters say about each filmmaker’s view of the common man in America? What do these characters tell us about corruption in the American political system (and the system’s ability to overcome corrupt actors)?

Both Tim Robbins’ Bob Roberts and Andy Griffith’s Lonesome Rhodes are Bad People. Each seeks to wield their influence over others in the pursuit of personal gain. Each sees what they believe in others to be ignorance, not as an opportunity to inform or engage, but as a weakness to exploit. While their individual strategies are specific to their respective storylines, there are some commonalities as to how they approach their goals, and how they are enabled in their pursuit by those around them. The actions of these characters speak to some of the risks involved in the perpetuation of a democracy.

Bob Roberts is a genuine conservative, with an interpretation of Republican dogma expressed to the nth degree. He is Gordon Gecko’s likeable second cousin, the one who gets invited to parties because he can play the guitar. He can get a little intense off-camera, but he’s young, he’s smart, he’s successful, he’s always smiling, he can sing, and did I mention that guitar? He also wants to win, and isn’t above the use of dirty tricks to do it. Those schemes – the smearing of Sen. Paiste, the staging of a shooting – are all executed with a smile and a catchy tune, because he knows how advantageous it can be to be seen as a nice guy.

Lonesome Rhodes is a pompous jerk. A media relations creation much like Cary Grant’s John Doe before it, Andy Griffith shares none of Grant’s charm. He’s the buddy from work you really wish you could shake sometimes. He’s bombastic, he’s crass – spending the evening with some woman, then proposing that same night to Marcia, then running off to Mexico to marry a 17-year old. He sees the people around him as tools to be manipulated- executives from which money can be pried, crowds from which rating points could be gained. He’s prone to drunken rages and womanizing behind the scenes, but he’s aggressively friendly when the cameras are rolling. He knows how to keep his masses in line, and he has a desperate need for their approval.

Together, these are men who know they are not perfect, and who know that a proper image must be maintained if they’re to continue earning the favor of their people. They’re willing to use others as tools of their subterfuge, and their quests for greater power are predicated on the assumption that their supporters were in some way deficient, or in need of paternalistic guidance. These supporters of theirs are less clear of a character, although they have appeared throughout this course. They are the “common man”, the Joe-the-Plumbers of yore. They are the bread and butter of America, they are The People, they are the unsung and silent moderate majority. All too often, they are cast as narrative targets, useful for the influence they can project when properly focused. That influence is commanding; it verges in Meet John Doe on the creation of a new political party. The common man is no one to be messed with. Yet all too often, it is the common man who is the creator of his own worst enemies. Both Lonesome Rhodes and Bob Roberts need their assistance for their schemes to succeed, both Rhodes and Roberts generously receive that support until something runs off the rails.

To the filmmakers, the common man would appear to be as flawed as their main characters. Capable of greatness when properly motivated, otherwise they’re susceptible to manipulation and prone to making short-sighted decisions. This is a sensible characterization, considering the evidence. America’s common man has been conned repeatedly over the years, with the occasional popular triumph over private avarice. He was sitting in the audiences for these performances. He is who the filmmakers were showing their worst-case scenarios to, so they could see the importance of being the heroes they were seeing on the screen. But he is a very tough nut to crack, so these lessons need to be repeated when fascism rises in Europe or when secret wars are fought in Southeast Asia. He is to some extent deserving of his travails, for his need to be reminded of the lessons of history. His unquestioning support for Lonesome Rhodes deserves to be followed with the pain of remorse. If there is a message to be taken from the entire curriculum, it’s that the common man’s character has seen almost no development over almost a century of filmmaking. The scams change and evolve over time, but we’re the same lumps today as those who enabled every other political corruption in our history.

A common element to these political stories is the exception- the common man who sees through the charade and sets himself to setting things right. It’s always these perceptive few on whom the freedoms of millions depend. In a nation of millions that can pose existential challenges for a world of billions, that’s a lot of pressure to be resting on Scooby and the gang year after year. One of these days, those darn kids are going to fail. This has been an unspoken message in each of these political films- what if the bad guys win? In Bob Roberts, we have just that outcome. Through the staging of events, the sentiment of the common man is swayed to victory by the forces of evil. The exception was right there and dead-on in his estimation of the danger, but the odds and the ammunition that were stacked against him were simply too great.

There will always be charismatic con men (and women), and we’re surely producing suckers faster than once per minute by now. There will always be a risk of manipulation, there are simply too many moving parts in a society of our size to keep a close eye on everything always, and that kind of attention would curb any number of civil rights besides. That we continue to elevate such charlatans speaks to the need for the messages of these films to be updated every few years as contemporary reminders; that we require reminders speaks to the need for a greater commitment on our part to the future of this enterprise.